Thus far, 2024 has been disorientating, exhausting, painful, maddening and swift. So swift. Too swift. Since doing my initial ADHD assessment over a year ago, I’ve been struggling to come to grips with the reality that I’ve been living with this condition my entire life, and it’s only just coming to light as I hurtle towards my 40s. I’ve also been grieving everything that ‘could have been.’ But I’ll write more about this on my other blog awyrdofherown.blog when possible.

Around midnight last night, too tired to read, I flickered around on Pinterest, looking for… I’m not even sure what. At some point, I landed on this knitted cape, leading me to Little Scandinavian, where I ended up on a post about The Scandinavian School in London, which looked like everything I would want for my daughter in a school, but whose gigantic fees were painful to read. It’s ridiculous, laughable even, that I let the fees of a school in a city where I don’t even live upset me.

I should have gone to bed then but didn’t. My mood was wounded. So I decided to scout out an image for the cover of my next book and ended up on The Public Domain Review – a treasury for the insatiably curious creative – which I combed through for Nordic bounty.

While I furiously bookmarked articles and added, to my already gridlocked desktop, old photographs of Norwegian fjords and Icelandic fishermen, I thought about producing an art appreciation post of some of the stuff I unearthed.

For the longest time, ‘art appreciation posts’ and ‘I-saw-these-things-and-thought-you-might-like-them-too’ posts were the lifeblood of my blogs. But then I gradually stopped making them, and I’ve missed making them, and am now on a mission to eradicate the idea from my head that making them ‘is not a good use of my time.’

The articles featured here in order are:

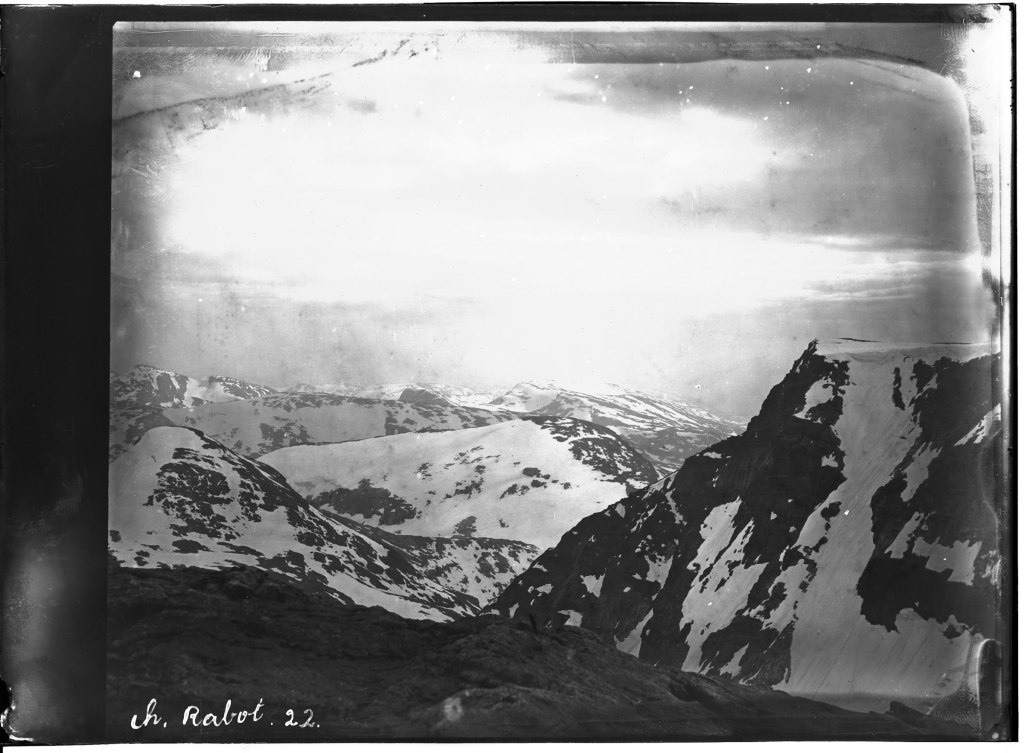

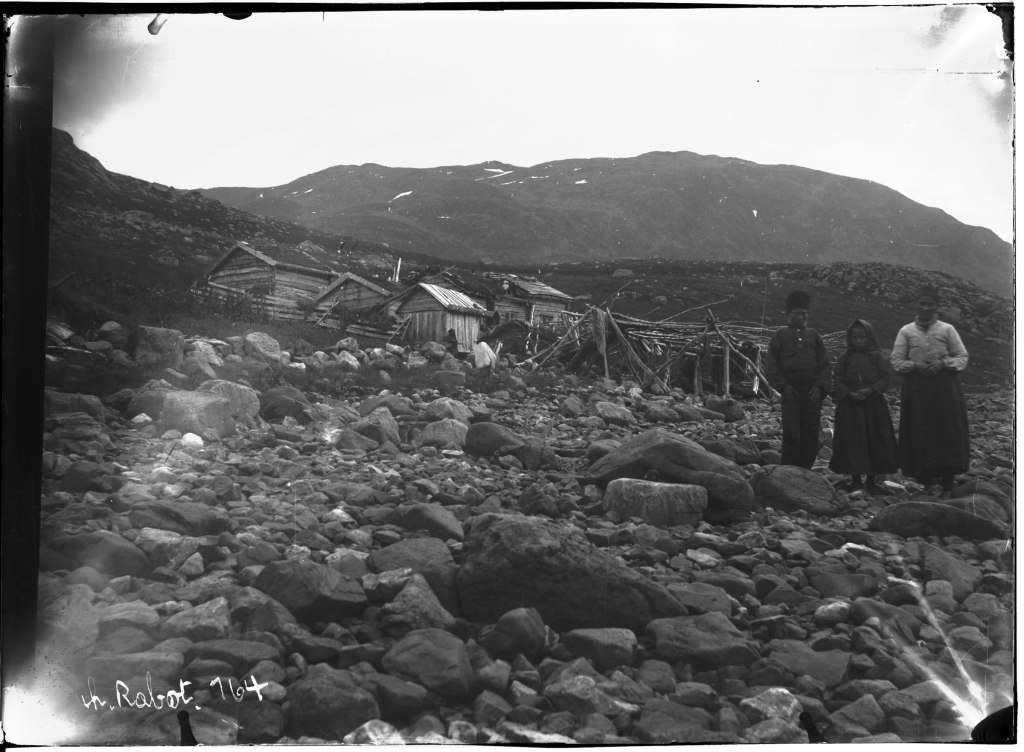

Masters of the Ice: Charles Rabot’s Arctic Photographs (ca. 1881)

Tempest Anderson: Pioneer Of Volcano Photography

Lantern Slides Of Norway (ca. 1910)

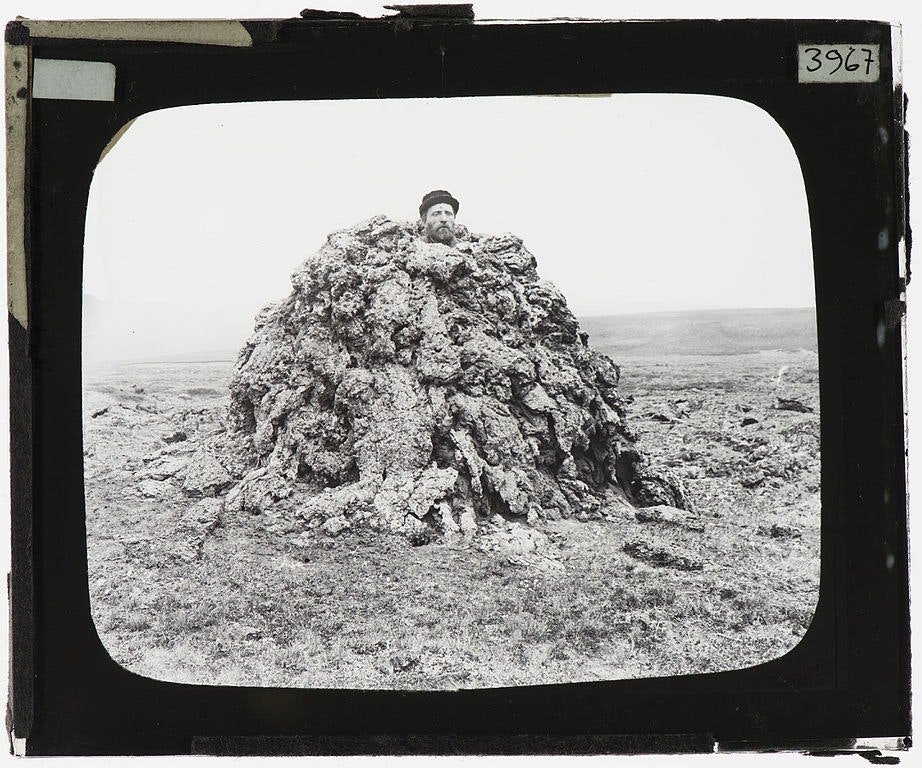

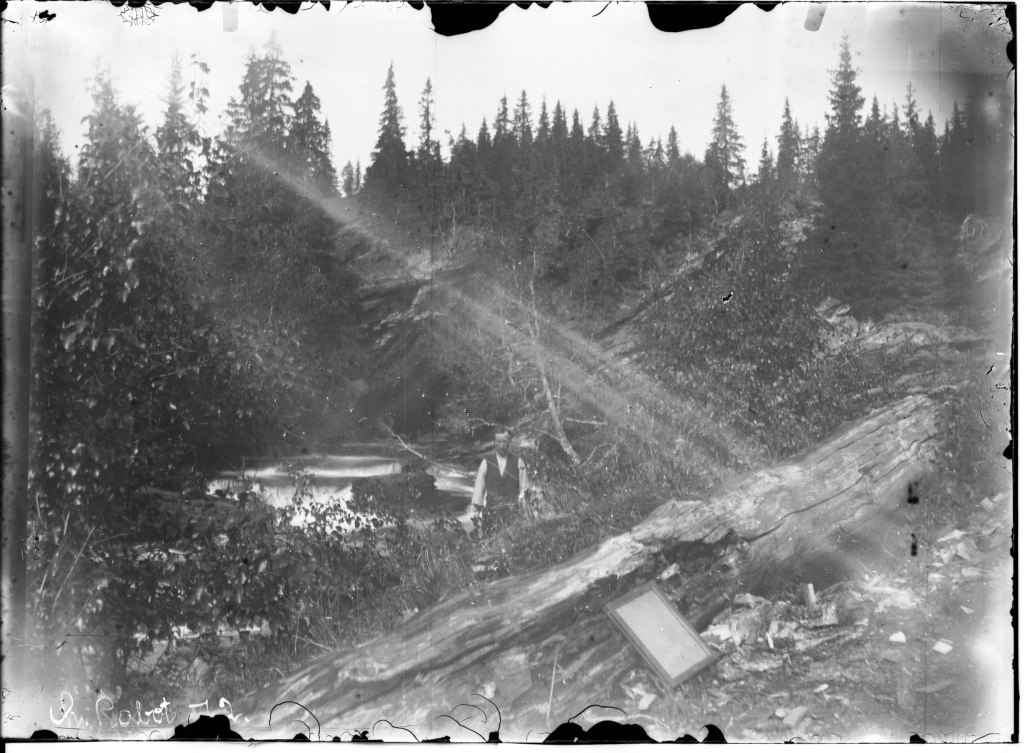

The first thing to catch my attention on The Public Domain Review was this striking, slightly sinister portrait of French geographer, glaciologist, and photographer Charles Rabot. This picture led me to a stupendously readable essay about Rabot by Erica X Eisen (whose other work I’m going to consume with gusto). Rabot had a ‘particular affinity for Norwegian culture…’ and his awe of ‘boral landscapes’ and ‘nostalgic yearning’ for the north is something I strongly identify with:

‘They are so beautiful, so magnificent, those deathly solitudes, so strange in their fleeting finery of brilliant colors, that they always leave one with a burning desire to see them again.’ – Charles Rabot

Eisen’s writing is astute and memorable – the following passage in particular ‘If there are any people to be seen in these snow-pied expanses, they are tiny afterthoughts so overwhelmed by the whiteness around them that any individuating features are obliterated completely — to the extent that these figures seem less like the protagonists of the shots and more like another accidental void bitten into the negative by the frost.’

The first person to climb Kebnekaise, Sweden’s highest mountain, in 1883, Rabot was also friends with the most swoon-worthy of Norwegian explorers, Fridtjof Nansen who’ll be much more thoroughly swooned over in another post where I’ll look at the bizarre but beguiling topic of fancying long-dead polar explorers.

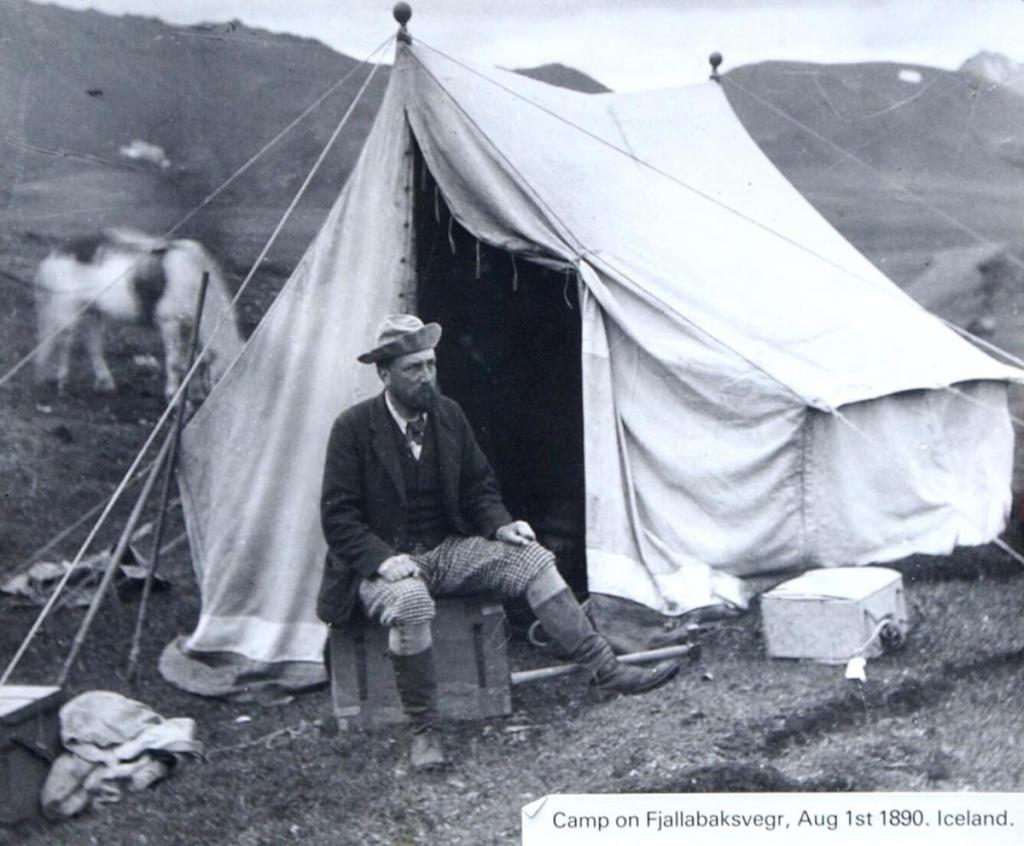

When I searched Iceland on The Public Domain Review, ‘ volcano chaser and pioneer of volcanic photography,’ Tempest Anderson showed up with one of the most gloriously surreal photographs I’ve ever seen.

Very much intrigued by the name Tempest, I was convinced there’d be a riveting origin story, so was a bit put out to find it was simply inspired by a prominent West Yorkshire family.

Yet there’s no doubt the man led a life not dissimilar to a windstorm—his list of occupations and accomplishments is…extensive. York-born and bred Anderson was a leading eye surgeon as well as a photographer, an inventor of photography equipment, a consulting physician to a lunatic asylum, a prison medical officer, a Sheriff of York… the list ploughs on. At 43, unmarried and restless, Anderson decided he’d use his spare time to study volcanology and chase volcanic eruptions. The photographs he shot in Iceland were taken using one of the earliest panoramic cameras, which, unsurprisingly, Anderson had developed himself.

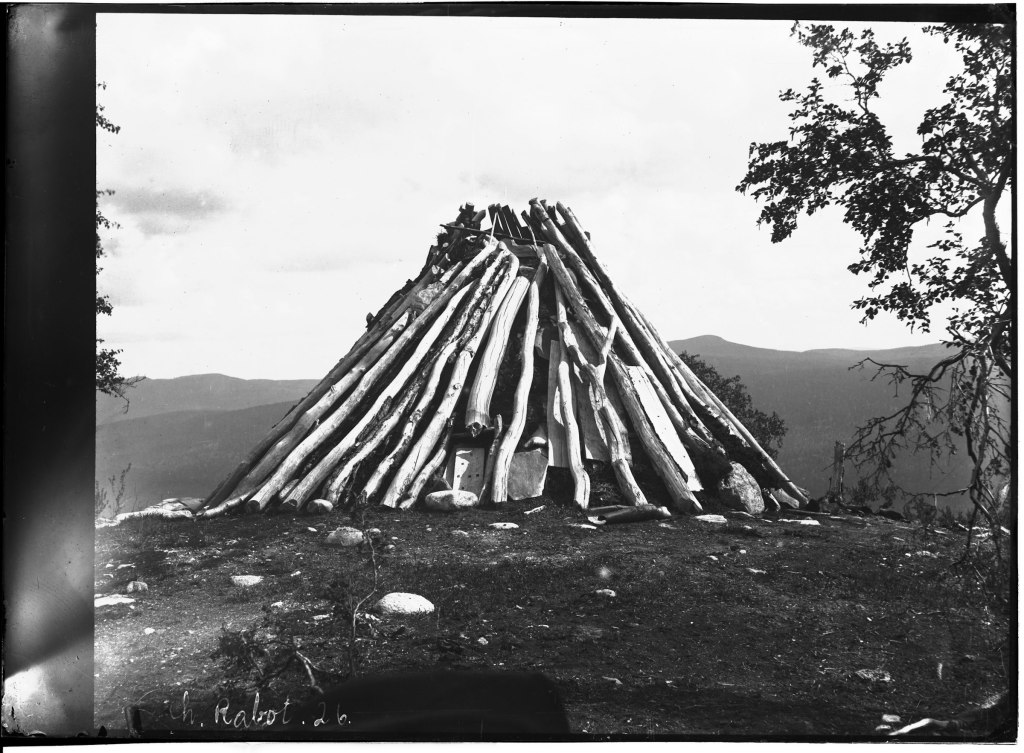

I’ll keep coming back to look at these lantern slides depicting Norway from the early 20th century, and I know each time I do, they’ll thrill me all over again. By the way, for full disclosure, I had to Google what a lantern slide is.

Lantern slides are positive, transparent photographs made on glass and viewed with the aid of a “magic lantern,” the predecessor of the slide projector. Lantern slide plates were commercially manufactured by sensitizing a sheet of glass with a silver gelatin emulsion. The plate was then exposed to a negative and processed, resulting in a positive, transparent image with exceptional detail and a rich tonal range. – Constance McCabe (National Gallery of Art.)

Produced by British photographers Samuel J. Beckett and P. Heywood Hadfield in my favourite part of Norway – Sogn og Fjordane (now known as Vestland) – these bold, crazily vivid lantern slides are held at the county archives in the fjord village of Leikanger, somewhere I’m going to absolutely seek out when I’m next over by way of the Sognefjord. Right now though, I’d very much like to know what the woman on the steps was thinking when this picture was made. Also, image 4 – haunted to my core.

Hadfield was a surgeon on a ship cruising the Norwegian fjords and an amateur photographer in his free time. Little is known about Beckett, but copies of books by both men (The Fjords and Folk of Norway by Beckett and Fjords of Norway A Cruise On The SS Ophir by Heywood) are available on Abebooks and eBay and are very kindly priced for books printed well over a hundred years ago.

More Recommended Reading From The Public Domain Review

Season’s Bleatings: Finnish Photographs of the Nuuttipukki (1928)

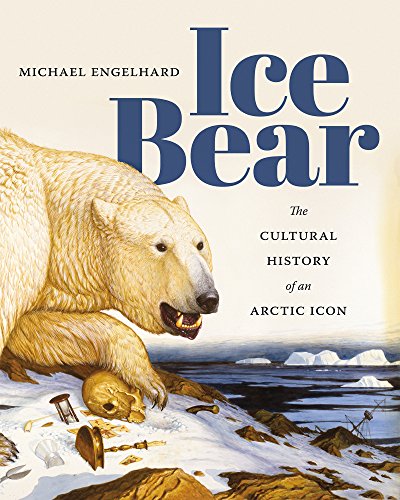

the High Arctic and it leaves no nerve unturned.

the High Arctic and it leaves no nerve unturned.