I’ve always found the frenzy of New Year’s Eve overwhelming. The relentless din of fireworks, the roaring countdown, the gargantuan pressure to have THE BEST TIME EVER. It’s just too much. Most of my New Year’s Eves have been spent in bed with my journal, picking over the past year in minute detail.

My perfect NYE would be in a forest cabin, hours from the closest town, where I’d experience absolute stillness well before and after midnight. If there did have to be noise, I’d much prefer to hear the pattering of hail, or a tree cracking in the cold or a raven cawing rather than fireworks and the deafening screams of HAPPY NEW YEAR!

But, this year, I was elated to be involved in the celebrations, which included fireworks and hugging at midnight, though thankfully no screaming. My Icelandic boyfriend invited me to spend the evening (though the evening lasts most of the day, with only four hours of light in Iceland at this time of year) with his family and girlfriend (our relationship is open).

I happily jumped head first into their traditions and felt much more upbeat than usual because the weather was suitably wintery – as it should be at the end of December. It was cold (-6.5 at times), and there was plenty of snow. (In a post on my blog, A Wyrd of her Own, I wrote about how out of sync I felt with the UK’s weather and the gigantic impact this had on my mood over Christmas.) In the UK, on NYE, it was wet, cloudy and blustery, with the temperature well into double figures.

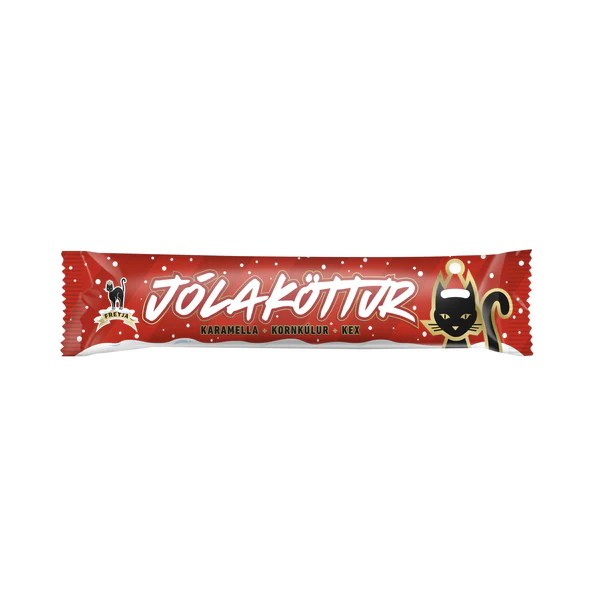

It’s tradition in Iceland to meet for a family meal between 6pm and 7pm. (We met at 6.30pm), and our meal was made up of typical Jól fare, including caramel-glazed potatoes, red cabbage, Waldorf salad (bound together with an incredible amount of whipped cream), endless bottles of Appelsín (orange soda) and cans of Malt og Appelsín (non-alcoholic malt beer mixed with aforementioned orange soda. Apparently it’s the taste of an Icelandic Christmas in a can.) There was also Toblerone ice cream. Curiously, decades ago in Iceland it became extremely popular as a festive dessert, and after snaffling down two helpings I can absolutely understand why.

After dinner and heartfelt debates about the existence of elves (according to my boyfriend’s uncles it’s simply not true that 54% of the population believes in them), we tramped across a field of deep snow to wonder at a gigantic communal bonfire. Known as Áramótabrennur, these fires have burned on NYE in and around Reykjavik since the 18th Century and originated from the belief that to have a clean start in the new year, you had to burn away the old year and all that it represented. We went to the bonfire at Geirsnef (you can ogle some of my photographs below), though we had several places to choose from in the Greater Reykjavik area. Across Iceland, around 90 bonfires are ignited on NYE.

There’s heaps of folklore linked to NYE in Iceland, and the folk tales of Jón Árnason, compiled in the 19th Century, talk of New Year’s Eve as the time when Hidden Folk would relocate their homes and become visible to people. Women would make the home spotless and light a candle in every corner. Once clean, the mistress of the house would walk around it and welcome any passing elves inside by saying, ‘Those who want to come may come, those who want to leave may leave, without harm to myself and my people.’ Leaving candles outside to guide the Hidden Folk was also customary.

Following the fire, we watched the annual comedy show, Áramótaskaupið (New Year’s Spoof). Broadcast on TV since 1966, it’s become such an central part of NYE celebrations that in 2002, an estimated 95.5% of the population tuned in to watch it.

After the show, from which I learned that Icelanders call Tenerife Tene (I find it amusing that Icelanders flee a cold volcanic island for a warm one), it was time to bring out the fireworks. Fireworks in Iceland differ from those elsewhere. They’re sold by ICE-SAR, the Icelandic Association for Search and Rescue (a volunteer-led organisation that saves upwards of 1200 people a year), who use the profits – which can reach hundreds of millions of kronur – to update their equipment.

We watched the kaleidoscopic display from a snowy hilltop. There was no being penned in by thousands of people screaming HAPPY NEW YEAR, and, for the first time, I genuinely enjoyed watching fireworks illuminate the new year.

There was absolutely zero pressure to have THE BEST TIME EVER, which enabled me, I’m sure, to really have fun. The evening ended with me feeling not overwhelmed but grateful, loved, and calmer than I can ever say I’ve been before on what I’d always thought of as the most highly-strung night of the year.