Autumn and its gales may be here (rejoice!), but I’m sharing this post regardless. I started writing about mosquitoes in September, but glanced away from the page, and October blew in. You know how it is, I’m sure.

A few years ago, I was celebrating Midsummer with family in Sweden. The weather was impeccable, the midsommarstång inspiring to behold, and the mosquitoes, for whatever reason (no repellent involved – I’d forgotten it), keeping a wide berth.

Well, keeping a wide berth from me. I was the only one not being savaged by summer’s least welcome players. My partner at the time – a man of Icelandic stock – was plagued worse than everyone and carries the scars to prove it.

Intriguingly, it may have been an odour in my sweat that was keeping them at bay. This lucky break was an isolated incident, though, as typically I’m swarmed and left with archipelagos of bites which swell to memorable heights.

It’s a little awkward to admit that I typically try to “shoo” mosquitoes away. On the occasion I’ve been beset with rage by their assaults and have slapped them to death, I’ve felt horrible. It’s difficult to reason with yourself when your neurodivergent empathy extends to biting insects. I may have felt differently had I been in Lapland, where mosquito swarms are biblical. I read a comment on Reddit about a couple getting out of their car, only to immediately dart back inside after spotting a fast-approaching mosquito cloud.

It’s not unusual for animals to spend so much time trying to escape mosquitoes that eating becomes impossible, and they starve to death. They can also die from blood loss – a swarm can take as much as 300 ml of blood from a single caribou in a one day.

Eero Järnefelt (1891)

I’m familiar with summer in the Nordics for the most part, but I’ve only recently learned that there are 50-60 species of mosquitoes in the Nordic countries alone. (Imagine how flabbergasted I was to discover over 3,000 species of mosquitoes exist worldwide.) I was also late to learn that it’s only female mosquitoes that feed on blood, while males feed exclusively on nectar.

Any standing water – from a puddle to a gutter to a tyre track – can host a breeding ground and then a nursery for developing larvae. Iceland’s lack of standing water is one reason mosquitoes haven’t managed to get a foothold.

“…as I made my way round their boggy breeding grounds they rose up to meet me in dark, swirling clouds, insinuating themselves in my clothes, choking my mouth and smothering every inch of my skin in bites. As I saw my hands beginning to swell, I ruefully consoled myself with the thought that at least I would not contract malaria, because my tormenters belonged to the genus Aedes which, happily, are not carriers of the disease.”

Walter Marsden, Lapland: The World’s Wild Places

*Soon after reading this – bear in mind Lapland was published in 1975 – I found out that mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria are spreading across Europe due to the climate crisis.

Early explorers of the North described mosquitoes as ‘worse than the cold,’ and ‘the one serious drawback of the north.’ I’m surely not the only one who relishes the vision of fumbling English gentry being set upon by mosquitoes, which have also been called ‘a frightful curse,’ as well as, quite fabulously, ‘…devils…armed with a lancet and a blood-pump…’

“In the summertime in Iqaluit, the capital city of the Inuit-administered Canadian territory of Nunavut, swarms of insects hover above the inhabitants like cartoonish clouds of gloom as they go about their day-to-day lives.“

Kate Press, Briarpatch Magazine

Many indigenous peoples of the Arctic viewed mosquitoes as something sent to ‘test endurance.’ For the Sámi, enduring harassment from mosquitoes was a way of proving hardiness. Young herders and hunters were expected to tolerate swarms during migration and calving season without excessive complaint. Jonna Jinton, an artist living in northern Sweden, endures the biting plague with humour, as demonstrated in this tongue-in-cheek mosquito meditation video.

In the Swedish town of Övertorneå, the community hosts the World Championship in Mosquito Catching, where the winner is the person who catches the most mosquitoes in just fifteen minutes, earning a cash prize and being crowned world champion.

In Finland, one of the Nordic countries I’ve yet to visit, these micro-predators have their own signs, and there’s a history of ‘mosquito bravado.’ Especially among the likes of fishermen and loggers who work amidst clouds of mosquitoes.

“We were breathing hard now, sweating in the afternoon haze and mobbed by a few thousand mosquitos each. Every square inch of exposed skin was smeared with Vietnam-issue jungle juice, stuff that dissolves plastic buttons and burns like acid in your eyes. It kept the actual blood loss down to a level that didn’t threaten death, but that wasn’t the real problem. It was the psychological warfare, airborne water torture. You felt the constant patter, and knew that your back was crawling with living grey fur, hundreds of relentless snouts probing for a chink in your armour. A hand wiped down a sleeve would come away sticky, smeared with corpses, and you strained them through your teeth.”

Nick Jans, The Last Light Breaking: Living Among Alaska’s Inupiat Eskimos

In the 1970s, the Inuk community leader Abe Opic wrote an essay called What it means to Be an Eskimo, where he, justifiably, compared white people to mosquitoes: “There are only very few Eskimos but millions of whites, just like the mosquitos. It is something very special and wonderful to be an Eskimo – they are like snow geese. If an Eskimo forgets his language and Eskimo ways, he will be nothing but just another mosquito.”

The Inuit have several stories about how mosquitoes came to be. The one you’re about to read was told to the Greenlandic/Danish explorer Knud Rasmussmun by Inugpasugjuk, a member of the Nattilingmiut Inuit community.

There was once a village where the people were dying of starvation. At last there were only two women left alive, and they managed to exist by eating each other’s lice. When all the rest were dead, they left their village and tried to save their lives. They reached the dwellings of men, and told how they had kept themselves alive simply by eating lice. But no one in that village would believe what they said, thinking rather that they must have lived on the dead bodies of their neighbours. And thinking this to be the case, they killed the two women. They killed them and cut them open to see what was inside them; and lo, not a single scrap of human flesh was there in the stomachs; they were full of lice. But now all the lice suddenly came to life, and this time they had wings, and flew out of the bellies of the dead women and darkened the sky. Thus mosquitoes first came.

If you do head to the far North, where the waters lie still and light lingers long into the night, wear long-sleeved shirts (doubling up is advised), socks, and trousers made from dense material. Wear a head net if you have access to one and remember that repellent loses its effectiveness when you begin to sweat. If you think you can escape them by going a bit further North, I should warn you that these blighters are now appearing in places where it was once too cold for them, which is, to put it lightly, worrying as fuck. We all know the North is warming, but the migration of mosquitoes makes it ever more painfully real.

I don’t want to abandon this post without attempting to lighten the mood (for you and me), so if you’re interested in seeing what it’s like to sit in a Finnish forest during summer, this gentleman can show you.

Sources

Atlas Obscura (If you want to know about the mosquito catching championship.)

Nunatsiaq News (Observations from Inuit about mosquitoes, including the story featured in this post.)

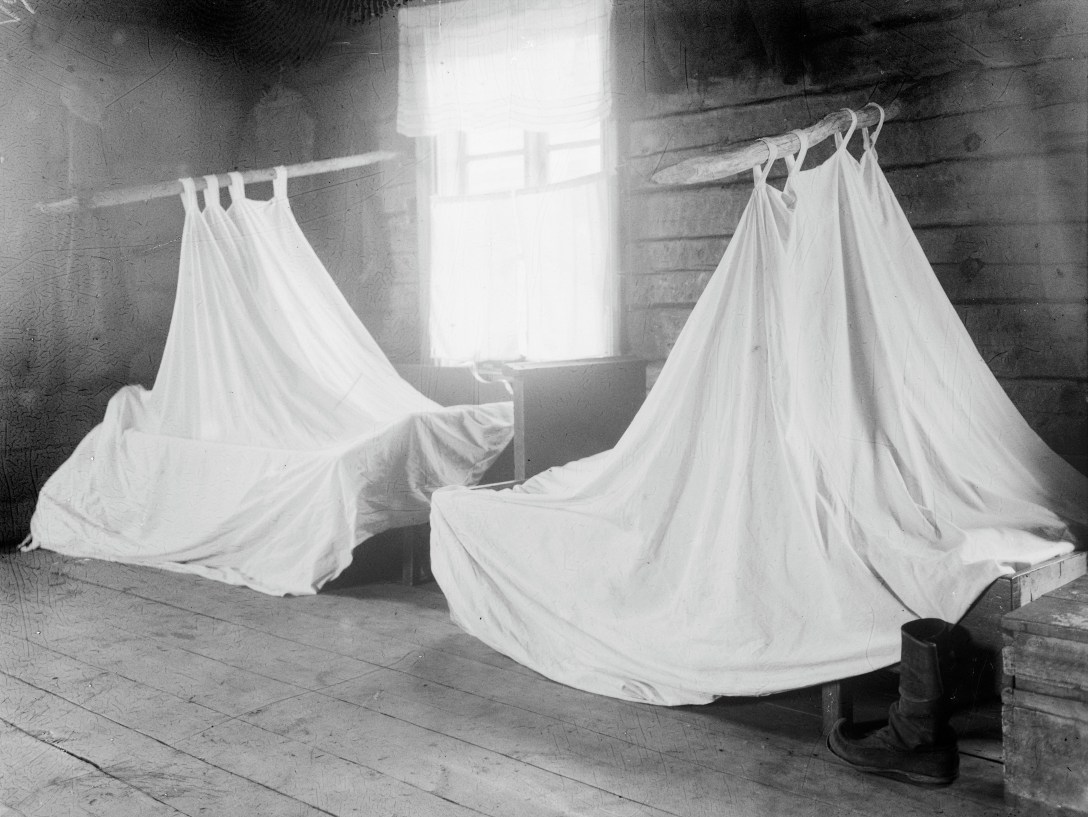

The featured image was taken by Samuli Paulaharju in 1937.