It was still dark at nine-thirty the other morning in Reykjavik (it would be well after ten before the sun shimmied up to provide the city with its scanty ration of daylight) when I bumbled outside to capture the looming Jólakötturinn (the Yule Cat) sculpture in all its ominous glory.

Every November since 2018, a five-metre-tall iron sculpture, decked out with 6,500 LED lights, depicting Gryla’s child eating floofy familiar (some attribute the inspiration for its ‘floofiness’ from the Norwegian Forest Cat) who eats children who don’t get new clothes for Jól has materialised in the centre of Reykjavik to herald in the season the traditional Icelandic way – with foreboding.

The sculpture cost the city a ‘sensible’ 4.4 million ISK and was fabricated by Austrian company MK Illumination. A garden centre owns it, and they lease it out each year to the city for a ‘steal’ at just over 3 million ISK.

Reykjavik’s Jól décor tends to be conventional, with the city reusing lights and garlands yearly. (Though I favour the cosy understatedness over most other cities I’ve seen ‘glowed up’ for Yuletide.) So, the sculpture’s arrival in 2018 was quite the talking point.

While the Yule Cat gathered much adoration (it was welcomed with a speech and a children’s choir), there was some backlash, too. One critic, Sanna Magdalena Mörtudóttir of the Socialists party, was critical of the city’s priorities and was furious the struggle of the city’s low-income families wasn’t brought up during the opening speech.

While cats have held a prominent role in Nordic society since the Viking Age, it’s unknown how long the Yule Cat has been around. Though it’s theorised he’s been prowling since the Dark Ages. We do know that he’s stalked written records since the 19th Century.

As Kathleen Hearons writes in Head Magazine, ‘Cats were the travelling companion of choice for Vikings – although not for sentimental reasons, but rather to kill mice and be skinned for their fur. Consequently, feline populations grew throughout the Nordic countries when the Vikings settled there. To this day, Reykjavik is “culturally a cat city,” according to Reykjavik Excursions. As of August 2022, there was a cat-to-human ratio of 1-to-10…‘

In bygone times, the threat of the Yule Cat would frighten children (and, without doubt, some adults) into finishing processing the autumn wool before Jól. By the Middle Ages, the export of wool from Iceland played a valuable role in the economy, and having a prosperous wool production was imperative.

Though this fear-mongering technique ensured laziness was all but eradicated in the last part of the year, it was also a superb encourager of family bonding, as everyone in the family had a role to play and would gather around the fire in the evenings to prepare yarn and knit.

In an article for the Reykjavik Grapevine, Ethnologist Árni Björnsson says, ‘After 1600, there are a lot of changes in Icelandic society. Folklore often mirrors what’s happening in society. So, it makes sense that Grýla and the yuletide lads are grimmer during this difficult time for Icelanders. In 1602, the Danes banned Iceland from trading with countries other than Denmark, and this was tough because Iceland relied on many imported goods. To make matters worse, the colder period in Iceland also sets in around 1600.

So, those things we call “jólavættir,” or supernatural beings of Christmas—including the yuletide lads, their ogress mother Grýla, and the Christmas cat—those elements were probably incorporated into the Christmas tradition to keep kids in line. Everyone was supposed to work hard to do all the things that had to be done before Christmas, and some people were lazy, you see. So it was said that if you weren’t diligent at working, the Christmas cat would come for you.’

In 1746, parents were banned by the King of Denmark from tormenting their children with stories of the Yule Cat, Gryla and her thirteen trouble-making lads as youngsters were becoming too afraid to leave their houses.

In 1932, a book was published by the poet Jóhannes úr Kötlum called Jólin koma (Christmas is Coming), and it featured a poem called Jólakötturinn which brings to life – though in the most family-friendly way – the goings about of the malicious moggy. An English translation was published in 2015 for the Icelandophiles out there.

You all know the Yule Cat

And that cat was huge indeed.

People didn’t know where he came from

Or where he went.

– The first stanza from Jólakötturinn

Following the publication of Jólin koma, the Yule Cat was, in the words of Áki Guðni Karlsson, writing for Icelandicfolklore.is ‘firmly established as part of an “old Icelandic” pantheon of Christmas beings for generations of Icelanders.’

You’ve probably encountered Bjork’s dungeon synthy musical adaptation of Kötlum’s poem at some point, though I’ve only recently discovered she wasn’t the first person to put it to music. That honour lies with the late Icelandic singer Ingibjörg Þorbergs. There’s also an exquisite version created by Icelandic folk duo Ylja.

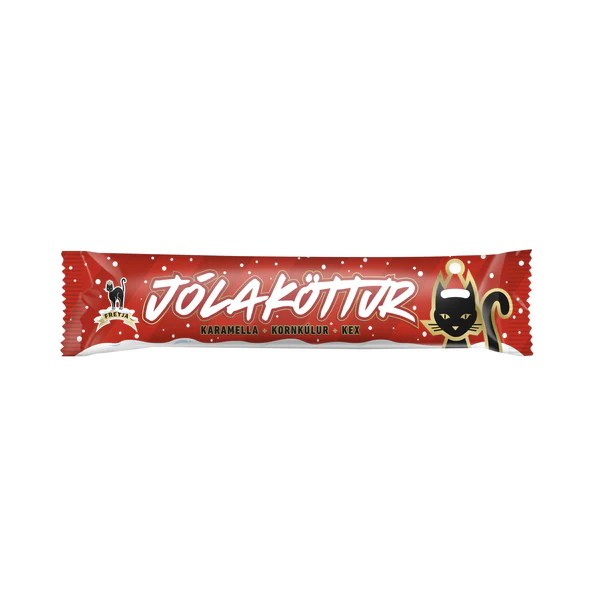

Like his mistress and her thirteen lads, the Yule Cat has long infiltrated Icelandic Christmas paraphernalia and even has his own chocolate bar, ‘Jólaköttur’ (the Christmas version of the famous chocolate bar Villiköttur), a delicious 50g beast of thick milk chocolate, caramel and biscuit all knobbled together with crisp rice.

The innovative chocolate company OmNom released a limited edition winter chocolate bar back in 2018 called Drunk Raisins + Coffee (which featured, among other things, green raisins infused with mandarin juice, cocoa beans from Tanzania, Icelandic milk and Austrian rum) in honour of the Yule Cat and in collaboration with the feral cat rescue organisation Villikettir.

On the OmNom website, Hanna Eiríksdóttir writes, ‘…stray and feral cats are neither evil nor frightening, and they definitely do not eat children. No one really knows how many cats in Iceland are feral or strays,they are thought to be in the thousands. In our minds, the Yule cat is the protector of these Icelandic stray and feral cats. The old folklore reminds us not to turn a blind eye to our little furry friends in need.’

I went back to the Yule Cat sculpture later on in the day. I saw togged-up kids catapulting themselves around in the straw pile surrounding the eternally pissed-looking puss, and now as I write this, I regret not sidling up to the parents and whispering to them, like the total weirdo I am, ‘So, do they think he eats harðfiskur now or…?’